If you have ever watched the epic film Zulu .....

|

| Colour Sergeant Bourne - As Seen In The Movie |

..... Then without doubt one of the strongest characters in it was Colour Sergeant Bourne. Oddly he never gets a Victoria Cross in the citations read out in the movies final scene.

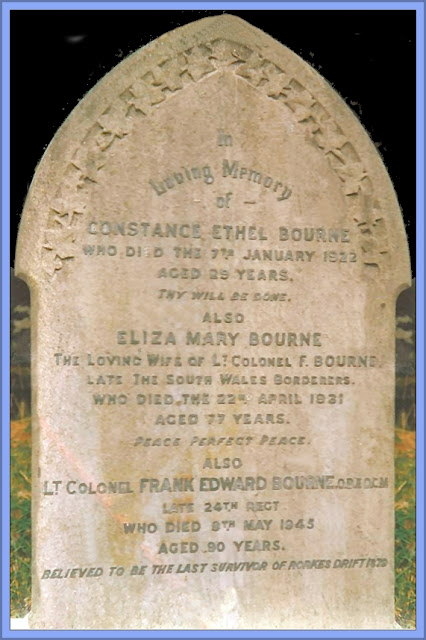

The character of Colour Sergeant Bourne was played by actor Nigel Green in the movie, who was 6'4" (1.93 m) of British oak (He had played Hercules in another classic Jason And The Argonauts, and Little John in the Sword of Sherwood Forest) ... however to say that the part was cast with some artistic licence, is something of an understatement. The real Frank Edward Bourne was in fact 5'6" in height, and some reports even say that he was just 5'3" (if so, he must have barely scraped in to the army). But let us give the man credit enough to know his own height "I stood only five foot six inches and was painfully thin".

He had joined the army at Reigate in December 1872, 8 months after his 18th birthday, enlisting in the 24th Regiment of foot, His first Sergeant Major, had a little joke by posting him to the 'A' Company. In those days the 'A' Company of any Regiment in any regiment was always called the 'Grenadier Company,' and was supposed to only have the biggest men in it.

He was paid 6d (six old pence = 5 pence new money) a day (or 3 shillings and 6 pence a week), of which 3 and a half pence a day was deducted for messing (food and drink) and washing, leaving 1 shilling, five and a halfpence a week for 'luxuries' .... he later said that he "went to bed every night hungry but quite happy, and it made a man of me".

By 1876 he had been promoted to Colour-Sergeant of the 100 strong 'B' Company by his Colonel, aged just 23, which made him the youngest senior NCO in the British Army ... this may have been partly because, despite coming from a poor family of eight in Balcombe, Sussex, England, he had been educated and could read and write, in stark contrast to many of the men with whom he had been serving. His advancement at such a tender age gave him the nickname of 'The Kid', but he was apparently well liked by the men under him, particularly as he acted as 'unpaid private secretary' to several of men who could barely read or write, and he deciphered and answered their letters home.

In February 1878 the Regiment was posted to South Africa, where it took part in a campaign against the Kausers in what was called the 'Kaffir War' by some. During this period, the regiment had been renamed as the South Wales Borderers, and so it was under that name that they illegally (Lord Chelmsford and Henry Bartle Frere had instigated the war without the approval of Her Majesty's Government), marched to war in January 1879 with the Zulu's, under the leadership of Lord Chelmsford ... the force was four thousand five hundred men, including thirteen Companies of the 24th Regiment of Foot.

When they crossed the Buffalo River in to Zulu territory, one company was left to guard the Hospital stores, and the Pontoons at the Drift aka Rorkes Drift. Colour Sergeant Bourne was the senior Non Commissioned Officer (NCO), under Lieutenants Gonville Bromhead of the 24th Regiment of Foot and John Chard of the Royal Engineers.

Lord Chelmsford led the rest of the men, including the regimental colours, marching band, wagon drivers, camp followers, servants and drummer boy in to Zulu territory, and for around half that force, to their utter annihilation at the battle of Isandlwana - Chelmsford had split his forces to scout out reports that the Zulus were further ahead and while he was away, some 20,000 Zulu warriors attacked the remainder of the British forces encamped on a mountain side (they did not follow standing orders to entrench or create a laager - circling of the wagons), consisting of about 1,800 British, colonial and native troops with approximately 350 civilians.

The Zulu's killed over 1,300 British and Native troops, whilst the Zulu army suffered anywhere from between 1,000 to 3,000 killed ... apparently some ammunition distribution problem occurred during the fighting because a Zulu later said that 'At first we could make no headway against the soldiers, but suddenly they ceased to fire, then we came round them and killed them with our assegais' ... suggesting that soldiers ran out of ammunition. The fact that the Zulus captured 400,000 rounds of ammunition (as well as three regimental colours, most of the 2,000 draft animals and 130 wagons plus sundry food, uniform supplies), suggests that there should have been no need for soldiers to stop firing.

|

| The Real Colour Sergeant Frank Bourne |

At the time, Bourne said he "was bitterly disappointed" to be in the company left behind .... but later they heard the sound of guns echoing over the hills, so they knew a battle had taken place. Refugees and a few survivors started turning up (the Zulus had ignored some civilians dressed in black, allowing them and a few patrol officers who happened to wear black riding jackets, to also escape) ... Bourne reported that 'one man whispered to me 'Not a fighting chance for you, young feller.'

With the two hours warning of the impending attack, the men fortified the station by creating firing loophole in the two buildings, and connecting the front of the Hospital with a stone cattle kraal by sacks of Indian corn and oats, and drawing up two Boer transport wagons, to join the front of the Commissariat Stores with the back of the Hospital. However, he was later to observe that this defence was not impregnable to a Zulu attack ..."as the sacks connecting the Hospital had to be laid on a slope of the ground he could safely have crept along, cut the sacks open with his assegais, the corn would have rolled out and he could have walked in." ... but that, thankfully the Zulus never once did this, or he would not have been around to tell his story.

He confirmed that the garrison strength at the Drift was "two combatant and six departmental Officers, and one hundred and thirty-three Non-Commissioned Officers and men (thirty-six of whom were sick), leaving about one hundred fighting men". They were later joined at about 3:30pm by an officer commanding a Troop of Natal Light Horse, having just got away from Isandhlwana (around 200 men in all including the Natal native horse) - they were ordered to send detachments to observe the Drift and Pontoons, and to place outposts in the direction of the enemy to check his advance. At 4.15pm, firing was heard and the Natal Light Horse officer returned to say that 'the enemy was very close' and that the 100 men in his Natal Light Horse detachment "would not obey his orders and had ridden off" ... then the detachment of 100 men of the Natal Native Contingent also "bolted", including their officer himself.

So the effective force level returned to 100 and events played out on much the same timeline as the movie shows it, desperate defence against attacks by around 3,000 Zulus, the hospital evacuation and fire with privates Hook, R. Jones, W. Jones and J. Williams being the last to leave, holding the door with the bayonet when all their ammunition was expended ... interestingly, Bourne stated that it was Zulu rifle fire, using the guns captured at Isandhlwana that was "the cause of every one of our casualties, killed and wounded .... there was hardly a man even wounded by an assegais - their principle weapon".

In all, the attack at Rorkes Drift lasted from 4.30pm until 4.00am the next morning ... The Zulus had withdrawn after that, but about 7 o'clock they reappeared again to the south-west, however, by luck, Lord Chelmsford had learned of the destruction of his camp at Isandhlwana after a Commandant Lonsdale had chanced to ride back to the camp, and having then been fired at by Zulus wearing British uniforms. He somehow escaped and was able to report the bad news to Lord Chelmsford.

Having found the camp empty of Zulu's, and just British bodies littering a stricken field, at dawn they had headed back to Rorkes Drift .... his approach caused the Zulu's to retire again. In all, the casualties of 12 hours of fighting (often at close quarters), was 17 British soldiers and others killed (all by gun fire), and 15 wounded. While the Zulus lost 351 (buried by the British), with their estimated wounded of between 400 to 500, which they removed under the cover of night. Many will have died elsewhere of their injuries.

However, many of the Zulu wounded were possibly killed by soldiers or the Natal Native Troops (European Settlers and Boers), in revenge later, if they were caught ... Trooper William James Clarke of the Natal Mounted Police described in his diary that "altogether we buried 375 Zulus and some wounded were thrown into the grave. Seeing the manner in which our wounded had been mutilated after being dragged from the hospital ... we were very bitter and did not spare wounded Zulus"... some of the soldiers also believed that they had killed a far greater number of Zulus during the battle ... Samuel Pitt, who served as a private in B Company during the battle, told The Western Mail in 1914 that the official enemy death toll was too low: "We reckon we had accounted for 875, but the books will tell you 400 or 500."

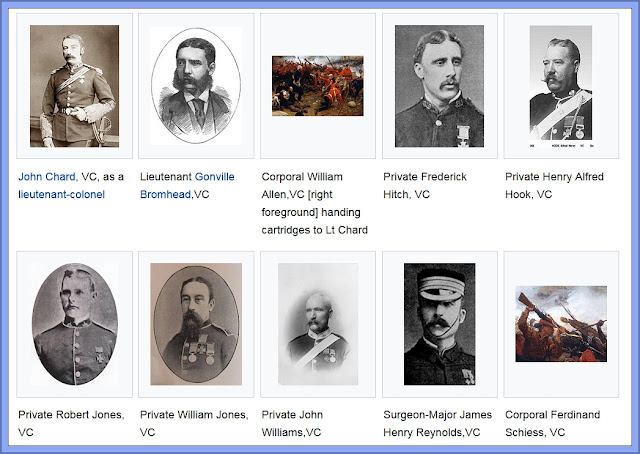

Seven Victoria Crosses (VC's) were given to one company of the Regiment (24th) South Wales Borderers:

- Private Henry Hook,

- Private Robert Jones,

- Private William Jones

- Private John Williams,

- Private Frederick Hitch,

- Corporal William Allen

- Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead (also promoted to Major)

- Lieutenant John Chard (also promoted to Major),

There was a reason why Victorian Britain conquered an empire. Tough little men like sergeant Bourne.

ReplyDeleteAgreed. Thanks for the comment

ReplyDelete